Usually, in response to the virus, the immune system produces neutralizing antibodies that protect against infection. However, scientists at Yale University found that patients with COVID-19 present autoantibodies directed against their bodies’ immune system’s tissues and cells. These autoantibodies disrupt the immune system, impair viral control, and increase the severity of the disease.

The researchers examined the blood plasma of 194 SARS-CoV-2 infected patients for the presence of autoantibodies against 2,770 human extracellular and secreted proteins. A healthy control group consisted of 30 PCR-negative SARS-CoV-2 medical workers.

Patients who underwent chemotherapy for malignant neoplasms, had metastatic diseases, underwent solid organ transplantation, and received immune-suppressing drugs, received plasma from those who recovered from COVID-19 as part of clinical trials from the subsequent analysis.

The researchers found that patients with COVID-19 had dramatically increased autoantibody reactivity compared to the uninfected control group. Simultaneously, autoantibodies against immunomodulatory proteins, including cytokines, chemokines, blood plasma, and cell surface proteins, are highly common. Autoantibodies directed against cells of the central nervous system, blood vessels, connective tissue, and extracellular matrix were also often present.

Meanwhile, the more autoantibodies were in the blood plasma, the more severe the COVID-19 disease was. In severe patients, autoantibodies to cells of the central nervous system, heart, liver, epithelium, and ion channels were present. Autoantibody levels correlated with inflammatory markers such as ferritin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and lactate, high levels associated with a worse prognosis for COVID-19.

Autoantibodies can alter the course of COVID-19, disrupting the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and causing direct tissue damage. Although COVID-19 patients showed high autoreactivity against extracellular and secreted body proteins, there were practically no COVID-19-specific autoantibodies that would distinguish COVID-19 patients from the uninfected control group.

In some patients, autoantibodies existed before infection with SARS-CoV-2, and the coronavirus increased their reactivity. That confirms the detection of autoantibodies with high reactivity within 10 days of the onset of symptoms. In other patients, autoantibodies appeared after infection with coronavirus.

Autoantibodies to interferon type I in patients with COVID-19

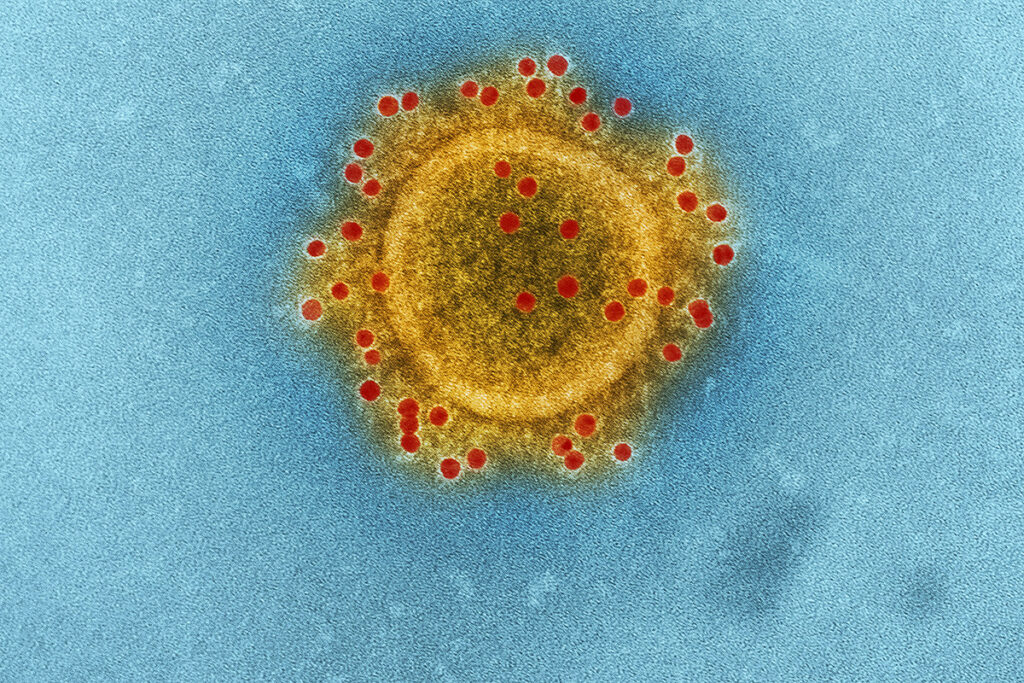

When the virus enters the body, the innate immune system recognizes the virus and triggers an antiviral response of type I and type III interferons. The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus can evade recognition by the immune system and alter the normal immune response. In severe cases of COVID-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, the response of type I interferons is delayed, causing inflammation and tissue damage.

In 5.2% of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, scientists found autoantibodies to interferon type I, and in patients with severe disease, these autoantibodies were more. In patients with type I interferon autoantibodies, the body was less clear of the virus, while patients without these autoantibodies could reduce the combined viral load over time.

In a mouse model, the researchers investigated the effects of antibodies on the interferon type I receptor (IFNAR). Mice pretreated with IFNAR antibodies were more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, as evidenced by increased weight loss and reduced survival. Also, these mice had a reduced number of activated antiviral defense cells.

These results show that autoantibodies that neutralize type I interferon inhibit innate antiviral responses, impair the ability to control viral replication, and increase the severity of COVID-19 disease.

Autoantibodies to the cells of the immune system in patients with coronavirus

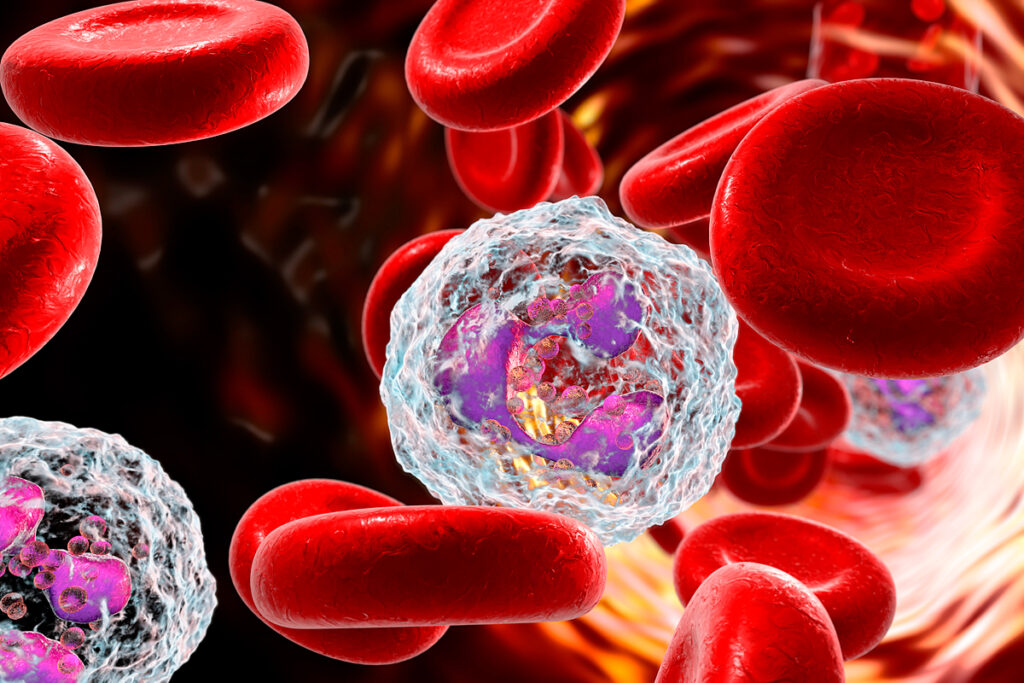

Autoantibodies that target the surface proteins of immune cells change the white blood cell composition. Patients with autoantibodies to B-lymphocytes had significantly lower frequencies of circulating B-lymphocytes than patients without these autoantibodies and with the control group.

B-lymphocytes produce antiviral antibodies. Patients with autoantibodies to B-lymphocytes had significantly lower levels of RBD IgM antibodies to SARS-CoV-2.

A patient with autoantibodies to CD38 protein had a reduced number of antiviral defense cells: NK-cells (natural killer cells), activated CD4+ t cells (t helper cells), and activated CD8+ t cells (t killer cells), all of which express CD38 protein on their surface.

Taken together, these findings suggest that autoantibodies targeting immune cell surface proteins are associated with the depletion of specific immune cell populations and may negatively affect the immune response to SARS-CoV-2.

Autoantibodies are responsible for the post-COVID syndrome

Many tissue autoantibodies Have been detected during post-COVID syndrome.

Post-COVID syndrome is The symptoms that persist After the virus is eliminated from the body. Among them:

- fatigue;

- shortness of breath;

- joint pain;

- chest pain;

- inability to concentrate and memory impairment;

- loss of taste or smell;

- trouble sleeping.

In some people, these symptoms persist for up to six months.

The question of what role specific autoantibodies play in creating post-COVID syndrome and whether they persist after the acute phase of COVID-19 deserves further study.

Source:

Diverse Functional Autoantibodies in Patients with COVID-19